Un monumento al momento

Medardo Rosso e le origini della scultura contemporanea

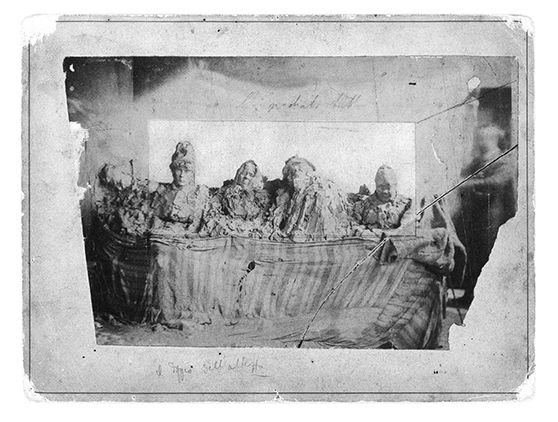

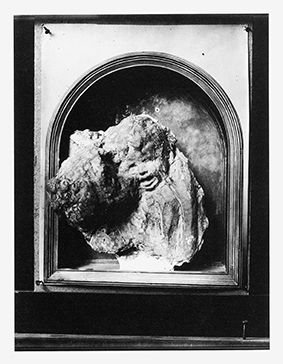

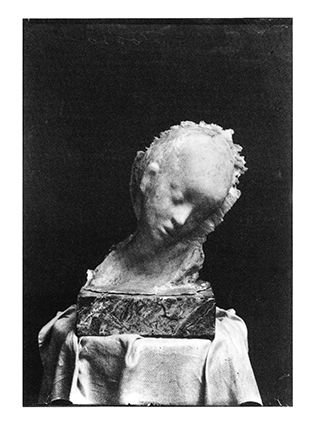

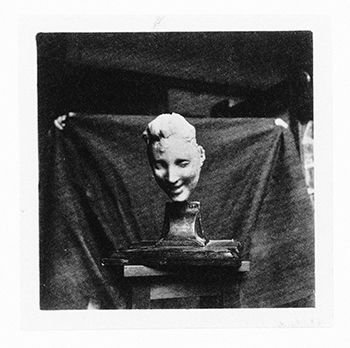

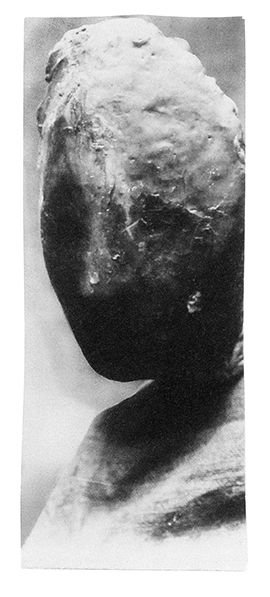

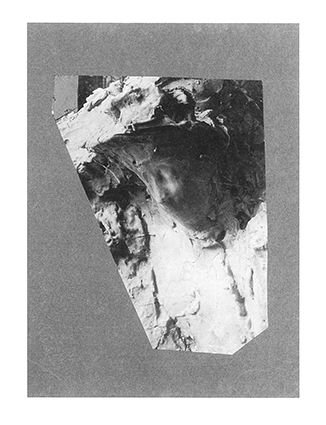

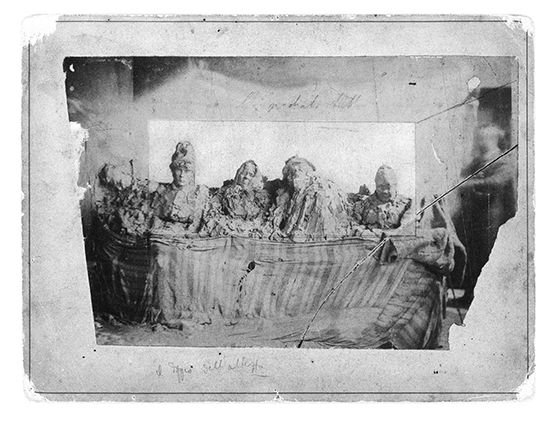

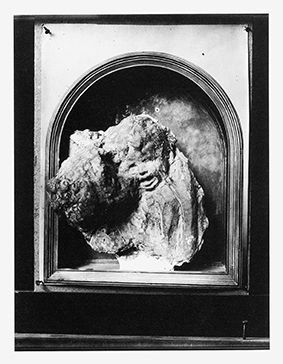

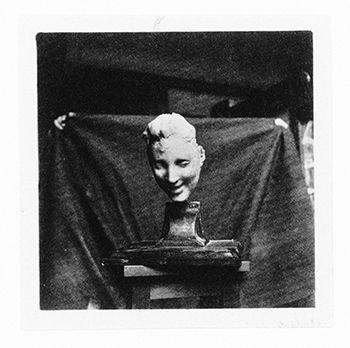

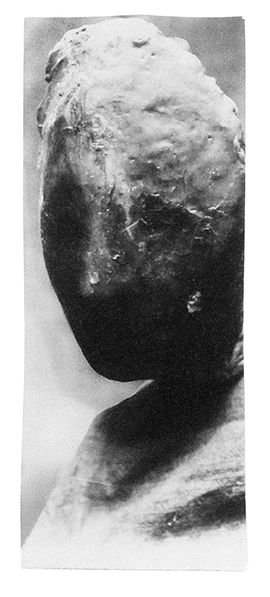

An artist loved by other artists, starting with Boccioni who praises his subversive power, Medardo Rosso (1858‒1928) produced revolutionary work that has never ceased to influence each new generation of sculptors. A forerunner to trends that were only fully developed in the 20th century, Rosso enjoyed extraordinary success after his death, making an indelible impression upon artists such as Brancusi, Giacometti and Moore, but also on many of his contemporaries: Fabrio stated that he owed him a substantial debt, and Anselmo, when faced with his wax sculptures, recognized how the material forged by Rosso vibrated from within, almost as if it had a beating heart of its own.

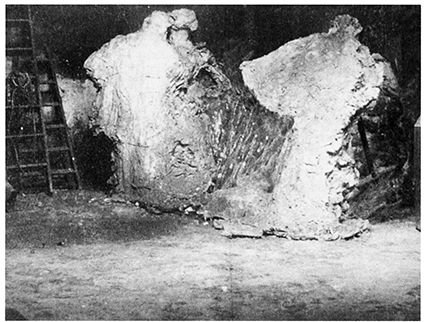

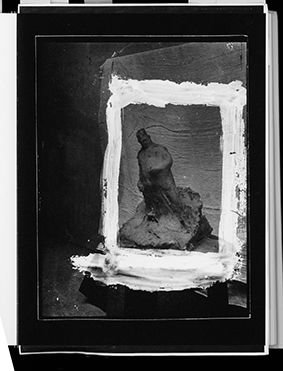

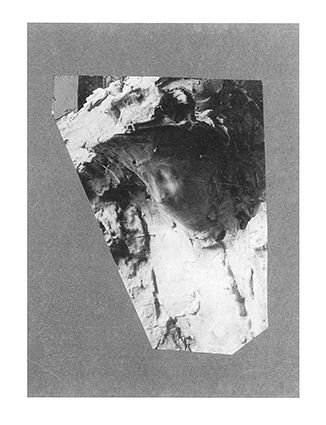

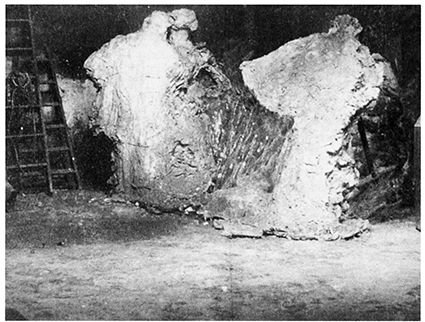

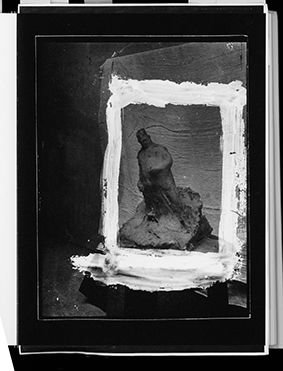

From the very outset, Rosso set himself an irreverent objective: to dematerialize monumental sculpture, which went from being eternal and celebratory to anti-heroic and able to capture a fleeting moment in his creations. However, he was also revolutionary in overstepping geographical barriers at a time when art was strongly defined within national borders. Having grown up after the Unification of Italy and disappointed by the empty promises of the Risorgimento, he left the country in 1889 for Paris, where he spent much of his life. An emigrant by choice and cosmopolitan by vocation, his fearless personality meant that he shunned any form of belonging, but made him receptive towards every modern stimulus, from new channels of communication to progress in photography, enabling him to draw upon a variety of visual sources and circulate his work as never before in his turn. What is more, by working on a small scale, Rosso turned the most static and heavy of the arts into an easily transportable product, in keeping with the unorthodox strategies he developed to promote his work.

This essay is the first to explore Rosso’s activity from a historical and transnational perspective, offering an alternative to the officially accepted account of the birth of modern sculpture. While Rodin has always been assigned the role of isolated and heroic innovator, Sharon Hecker upholds the important part played by an artist who pioneered many practices that have become commonplace in the global artistic vocabulary today.

Textual index

Nota dell’autrice

Introduzione. Medardo Rosso: una storia delle origini

1. Per un approccio antieroico alla scultura moderna

2. Monumenti senza eroi

3. “Scultore impressionista”? L’impossibilità di classificare Rosso

4. Internazionalismo e sperimentazione

5. L’esperienza artistica della migrazione

6. La precaria prospettiva dello straniero

7. Vedere ed essere visto. Ripensare l’incontro tra artista, opera e pubblico

8. Artista itinerante. La ricerca di un riconoscimento internazionale

Postfazione

Un monumento al momento